Received: Mon 31, Jul 2023

Accepted: Tue 29, Aug 2023

Abstract

Background: We aimed to compare the results of open surgery and double-port laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal suturing repair for the treatment of morgagni hernia (MH). Methods: Twenty-two patients with MH who were operated on in our clinic between January 2012 and January 2023 were included in the study. Patients were divided into two groups according to the surgical technique as open surgery (OS) (n=14) or laparoscopic surgery (LS) (n=8). Retrospective comparisons were made between the groups' demographic information, surgical method used, defect size, operation time, hospital stay length, cost, postoperative problems, and recurrence. Results: There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of gender, defect size, and costs (p>0.05). The mean age of the patients in the LS group (101 ± 68.3 months) was significantly higher than that of the OS group (23 ± 18.2 months) (p=0.005). It was determined that the operation time of the LS group (33.8 ± 3.6) was significantly shorter than that of the OS group (50.8 ± 6.5) (p<0.01). Moreover, the LS group’s length of hospitalization (1.6 ± 0.9) was significantly lower than the OS group’s (2.8 ± 0.7) (p=0.027). Conclusion: Double-port laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal suturing repair technique is a reliable technique that can be preferred over open surgical repairs due to its shorter operative time and hospital stay, ease of application, better cosmetic results, and no cost difference.

Keywords

Morgagni hernia, children, laparoscopic repair, double port, open surgery

1. Introduction

Morgagni hernias (MH) are a rare congenital anomaly originating from the anteromedial part of the diaphragm and are usually on the right side. Abdominal organs herniated from the defect in the retrosternal area to the thorax. It constitutes 3-5% of all diaphragmatic hernias [1, 2]. The disease was first described in 1761 and is named after the Italian anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni [2]. Since the disease is usually asymptomatic, it is diagnosed late. Frequent lower respiratory tract infections and pain are prominent in symptomatic cases. It is usually diagnosed on radiographs taken during lung infection [3].

The known classical treatment of the disease is the repair of the defect by laparotomy. With the widespread use of laparoscopy after the 1990s, more minimally invasive techniques have begun to be preferred in the treatment of the disease [2, 4]. We aimed to compare the double-port laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal suturing repair technique and open surgical repair in MH.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Morgagni hernia (MH) cases that were operated on in our clinic between January 2012 and January 2023 after obtaining ethical approval from the ethics committee of Selcuk University Faculty of Medicine were reviewed retrospectively (2023/59). Twenty-two cases operated for MH were included in this study. The patients were divided into two groups according to the surgical technique as open surgery (OS) (n=14) or laparoscopic surgery (LS) (n=8). Retrospective comparisons were made between the patients' (groups') demographic information, surgical method used, defect size, operation time, hospital stay length, cost, postoperative problems, and recurrence. The statistical analysis was carried out using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher test for categorical variables.

3. Laparoscopic Surgery Technique

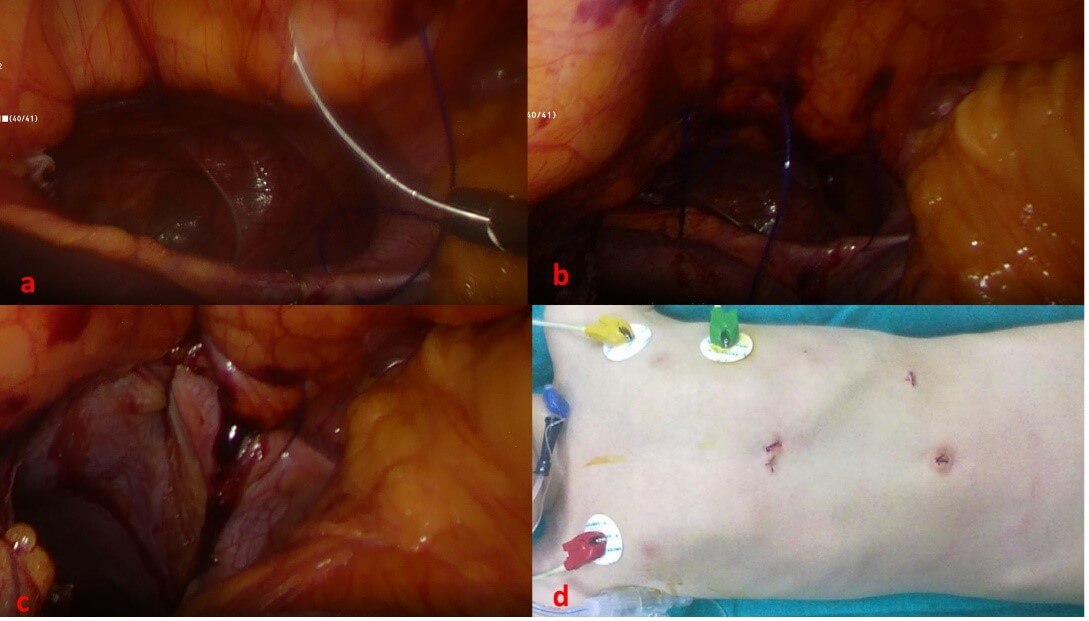

The patient is administered general anesthetics, and endotracheal intubation is carried out. A 5 mm trocar is entered into the abdomen with an open technique by making an upper umbilical incision and the pneumoperitoneum is created with 8 mm HgCO2 insufflation. Then, another 5 mm trocar is placed in the left hypochondrium from the midclavicular line. The intestines that were discovered during examination in the hernia sac on the anterior thoracic wall are transferred to the abdomen. A 2-mm skin incision is created in accordance with the defect's projection and a 2/0 polyester suture is taken through the incision into the abdomen. The needle, which is caught with a grasper in the abdomen with the tip pointing upwards, is taken out of the abdomen through the same incision, passing through the lower and upper diaphragmatic rims, where the defect is located, respectively. According to the width of the defect, sequential millimetric incisions are made, 3-4 sutures are placed in the diaphragm, and the sutures are tied in sequence. Thus, the hernia repair is completed. A 2/0 absorbable suture is used to mend the fascia after the suture knots are implanted under the incision and the trocar is taken out. Sutures made of subcutaneous absorbable 5/0 are used to seal skin incisions (Figure 1).

4. Results

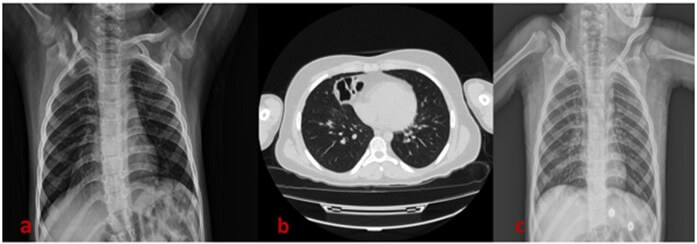

In our study, the data of 22 patients who were operated for MH were compared statistically. The mean age of the patients was 45.94 ± 52.3 months, and the female: male ratio was 9:13. 14 patients presented with a chest infection, which was recurrent in 9 of them. four individuals reported nonspecific respiratory symptoms and asthma-like symptoms, respectively. The diagnosis for the remaining 4 patients was made based on a chest x-ray because they had no symptoms. In all of the cases included in the study, non-contrast thorax tomography was performed to confirm the diagnosis, and control chest x-ray were performed in all cases after the operation (Figure 2). There were 14 patients in the OS group and 8 patients in the LS group. The demographic data, defect size, operation time, cost, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and recurrence of the patients are detailed in (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of gender, defect size, and costs (p>0.05). The mean age of the patients in the LS group (101 ± 68.3 months) was significantly higher than that of the OS group (23 ± 18.2 months) (p=0.005). It was determined that the operation time of the LS group (33.8 ± 3.6) was significantly shorter than that of the OS group (50.8 ± 6.5) (p<0.01).

TABLE 1: The data of patients according to the groups.

|

|

Open Surgery (OS)

Group n: 14 |

Laparoscopic Surgery

(LS) Group n: 8 |

p-Value |

|

F/M |

6:8 |

3:5 |

|

|

The mean age (mo) |

23 ± 18.2 |

101 ± 68.3 |

0.005 |

|

The mean defect size

(cm) |

5 ± 1.7 |

5 ± 1.5 |

0.506 |

|

The mean duration of

operation time (min) |

50.8 ± 6.5 |

33.8 ± 3.6 |

<0.001 |

|

Length of hospital

stay (d) |

2.8 ± 0.7 |

1.6 ± 0.9 |

0.027 |

|

Cost Turkish lira

(TL) |

4,332 ± 2406 |

4,208 ± 1950 |

0.99 |

|

Postop complications |

2 (14.2%) |

0 |

0.27 |

|

Recurrence |

1 (7.1%) |

1 (12.5%) |

0.612 |

Moreover, the LS group’s length of hospitalization (1.6 ± 0.9) was significantly lower than the OS group’s (2.8 ± 0.7) (p=0.027). No LS patient needed to transition to open surgery. No intraoperative complications were observed in either group. Brid ileus developed in one patient in the CS group at the postoperative 7th month but did not require surgery, it was treated conservatively. Another patient in the same group developed an incisional hernia and was operated on again at the postoperative 10th month. During follow-up, recurrence was detected in one patient in the LS group. This patient underwent open surgical repair 6 months after the operation. Upon recurrence of the patient, the mesh was applied with an open surgical technique in the 9th month after the last operation. There was no problem in the long-term follow-up of the patient. This patient had down syndrome and immunodeficiency. One patient in the OS group was reoperated 8 months postoperatively due to the recurrence of the disease.

The information about the comorbidity of the patients, the sides of the defect, and herniation organs through the defect are given in (Table 2). Among the patients included in the study, 10 (45.4%) had trisomy 21, 4 (18.1%) had immunodeficiency, 4 (18.1%) had congenital heart disease, 1 (4.5%) had esophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula, and 2 (9%) had hydrocephalus. The defect was on the right side in 15 (68.2%) patients, on the left side in 4(18.2%) patients, and bilateral in 3 (13.6%) patients. All patients had colon herniation. However, omentum hernia in eight patients, cecum in two patients, small intestine in four patients, and liver in two patients were observed.

TABLE 2: Clinical features of patients.

|

F |

9 (40.9%) |

|

M |

13 (59.1%) |

|

Co-morbidities |

|

|

Down Syndrome |

10 (45.4%) |

|

Immunodeficiency |

4 (18.1%) |

|

Esophageal Atresia |

1 (4.5%) |

|

Hydrocephalus |

2 (9%) |

|

Congenital Heart Disease |

4 (18.1%) |

|

Surgical Technique |

|

|

Open Surgery |

14 (63,6%) |

|

Laparoscopic Surgery |

8 (%29.4) |

|

Side of Defect |

|

|

Right |

15 (68.2%) |

|

Left |

4 (18.2%) |

|

Bilateral |

3 (13.6%) |

|

Herniated organs |

|

|

Colon |

22 (%100) |

|

Cecum |

2 (9%) |

|

Small intestine |

4 (18.1%) |

|

Omentum |

8 (36.3%) |

|

Liver |

2 (9%) |

5. Discussion

MH can be discovered either incidentally or as a result of vague gastrointestinal complaints; more commonly, it causes respiratory symptoms, which can be severe during infancy [5]. The situation was similar in our series. Most of the patients had a history of recurrent lung infections and therefore hospitalization. In only 4 cases, the disease was detected after an incidental chest x-ray.

Another interesting feature of morgagni hernia is the presence of 30-50% associated congenital anomalies [6]. The most common congenital anomalies associated with MH are Down syndrome and congenital heart diseases [6,7]. In our series, we see a very high rate of down syndrome cases (10/22, 45.4%). This strong correlation between trisomy 21 and the hernia of morgagni may be due to impaired dorsoventral migration of rhabdomyoblasts from paraxial myotomes, which is brought on by enhanced cellular adhesiveness in trisomy 21 [7, 8]. Congenital heart disease was present in 4 (18.1%) cases, esophageal atresia in 1 (4.5%) case, and hydrocephalus in 2 (9%) cases. An interesting association of MH in our study is immunodeficiency. Immunodeficiency was present in 4 (18.1%) of our cases. All immunodeficiency cases had down syndrome. This suggests that immunodeficiency is primarily associated with down syndrome, not with MH.

In our study, the number of male cases was higher than females (13/9), consistent with the literature [4, 9]. While the mean operative age of the OS group (23 ± 18.2 m) was consistent with the literature, the mean operative age of the LS group (101 ± 68.3 m) was significantly greater (p=0.005). In our study, the mean defect sizes of both groups were close to each other (OS: 5 ± 1.7, LS: 5 ± 1.5), and these dimensions were consistent with the 3-11 cm reported in other studies [4, 9]. Although it was reported in the literature that the groups that underwent laparoscopy were less costly than those that underwent open surgery, no statistically significant cost difference was observed between the groups in our study (OS: 4.332 ± 2406 TL, LS: 4.208 ± 1950 TL) (p=0.99) [10]. We think that this is due to the inconsistent cost differences that have developed due to the rapidly changing exchange rates in our country.

The length of hospital stay of the patients was statistically significantly shorter in the LS (1.6 ± 0.9) group than in the OS group (2.8 ± 0.7), similar to the literature (p=0.027) [4, 10, 11]. Between 5-10% of postoperative complications have been reported in the literature [12]. In our study, while the complication rate was 14.2% in the OS group, no complications were observed in the LS group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative complications (p=027). While the recurrence rate in open surgical repair of MH has been reported as 42 to 50%, this rate has been reported between 0 to 42% in laparoscopic repairs in the literature [2, 13, 14]. In our study, recurrence was reported after surgery in one patient in each group, and no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (p=0.612).

When the operation times between the two groups were compared, it was seen that the operation time of the LS group (33.8 ± 3.6) was statistically significantly lower than the OS group (50.8 ± 6.5) (p<0.001). In our study, it can be said that laparoscopic repair is more advantageous because the operation time and hospital stay were shorter in the LS group, and the cost, complication and recurrence rates did not differ. Another important reason that makes laparoscopic repair advantageous is the more reasonable cosmetic appearance. The majority (90%) of morgagni hernia occurs on the right side, 2% on the left side, and 8% are bilateral [15]. Due to the left side's greater pericardial connection to the diaphragm, which provides support and protection, morgagni hernias on the left side are more uncommon [15]. In our series, 15 patients (68.2%) had the defect on the right side, 4 patients (18.2%) had it on the left, and 3 patients (13.6%) had it on the bilateral.

The aim of the surgery in MH is to pull the herniated bowel loops into the abdomen and repair the defect. The standard approach in MH is open surgical repair. The first successful laparoscopic surgery of a morgagni hernia in a kid was documented by Georgacapulo et al. in 1997 [16]. After this minimally invasive procedures such as laparoscopic-assisted repair have been described and successfully applied [17, 18]. A few of these minimally invasive methods include patch closure of diaphragm defects, primary suture repair, primary repair with staples, laparoscopic extracorporeal procedure, transabdominal suture placement, knotting devices, hernia sac implantation, robot-assisted laparoscopic repair, and thoracoscopic repair [19-23]. Most of the laparoscopic interventions described in the literature were performed using 3 ports entered from the umbilicus and from both sides [24, 25]. The authors describe the single-post repair performed the operation by placing 3 surgical instruments in a single post. Oztorun et al. also introduced the optical forceps-assisted single-port laparoscopic PIRS repair technique to the literature [10]. The use of the laparoscopic double port extracorporeal suturing repair technique that we applied to our patients has not been found in the literature. In this respect, our work is very valuable.

6. Conclusion

MH repair with double-port laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal suturing repair technique involves shorter operation time and hospital stay compared to open surgical techniques. However, it can be preferred over other techniques because it is more advantageous in terms of cosmetics compared to open surgery and other laparoscopic techniques, can be applied easily, and has equal complication and recurrence rates.

Acknowledgments

None.

Competing Interests

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: i) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, ii) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, iii) final approval of the version to be submitted.

REFERENCES

[1] Ahmed H Al-Salem “Congenital hernia

of Morgagni in infants and children.” J Pediatr Surg, vol. 42, no. 9,

pp. 1539-1543, 2007. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[2] Yew-Wei Tan, Debasish Banerjee, Kate

M Cross, et al. “Morgagni hernia repair in children over two decades:

Institutional experience, systematic review, and meta-analysis of 296

patients.” J Pediatr Surg, vol. 53, no. 10, pp. 1883-1889, 2018. View

at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[3] John D Horton, Luke J Hofmann,

Stephen P Hetz “Presentation and management of Morgagni hernias in adults: a

review of 298 cases.” Surg Endosc, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 1413-1420, 2008.

View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[4] Ahmed H Al-Salem, Mohammed

Zamakhshary, Mohammed Al Mohaidly, et al. “Congenital Morgagni's hernia: a

national multicenter study.” J Pediatr Surg, vol. 49, no. 4, pp.

503-507, 2014. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[5] W J Pokorny, C W McGill, F J Harberg

“Morgagni hernias during infancy: presentation and associated anomalies.” J

Pediatr Surg, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 394-397, 1984. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[6] Murat Kemal Cigdem, Abdurrahman Onen,

Hanifi Okur, et al. “Associated malformations in Morgagni hernia.” Pediatr

Surg Int, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 1101-1103, 2007. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[7] R C Parmar, M S Tullu, S B Bavdekar,

et al. Morgagni hernia with Down syndrome: a rare association -- case report

and review of literature. J Postgrad Med, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 188-190,

2001. View at: PubMed

[8] L H Honoré, C P Torfs, C J Curry

“Possible association between the hernia of Morgagni and trisomy 21.” Am J

Med Genet, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 255-256, 1993. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[9] Giuseppe Lauriti, Elke

Zani-Ruttenstock, Vincenzo D Catania, et al. “Open Versus Laparoscopic Approach

for Morgagni's Hernia in Infants and Children: A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis.” J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, vol. 28, no. 7, pp.

888-893, 2018. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[10] Can İhsan Öztorun, Doğuş Güney, Hayal Doruk, et al. “Comparison of Optical

Forceps-Assisted Single-Port Laparoscopic PIRS and Open Surgery in Morgagni

Hernia Repair.” Eur J Pediatr

Surg, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 127-131, 2022. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[11] Vahit Ozmen, Feryal Gün, Coskun

Polat, et al. “Laparoscopic repair of a morgagni hernia in a child: a case

report. Surgical laparoscopy, endoscopy & percutaneous techniques.” Surg

Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, vol, 13, no. 2, pp. 115-117, 2003. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[12] Ciro Esposito, Maria Escolino,

Francois Varlet, et al. “Technical standardization of laparoscopic repair of

Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia in children: results of a multicentric survey on

43 patients.” Surgical endoscopy, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. 3320-3325, 2017.

View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[13] Gratiana Alqadi, Amulya K. Saxena

“Laparoscopic Morgagni hernia repair in children: systematic review.” Journal

of Pediatric Endoscopic Surgery, vol. 1, pp. 85-90, 2019. View at: Publisher Site

[14] Osama A. Bawazir, Anies Mahomed,

Amira Fayyad, et al. “Laparoscopic-assisted repair of Morgagni hernia in

children.” Annals of Pediatric Surgery, vol. 16, pp. 1-7, 2020 View at: Publisher Site

[15] Aayed Alqahtani, Ahmed Hassan

Al-Salem “Laparoscopic-assisted versus open repair of Morgagni hernia in

infants and children.” Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, vol. 21, 1,

pp. 46-49, 2011. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[16] P Georgacopulo, A Franchella, G

Mandrioli, et al. “Morgagni-Larrey hernia correction by laparoscopic surgery.” Eur

J Pediatr Surg, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 241-242, 1997. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[17] Mohammad Saquib Mallick, Aayed

Alqahtani “Laparoscopic-assisted repair of Morgagni hernia in children.” J

Pediatr Surg, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 1621-1624, 2009. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[18] Carrie A Laituri, Carissa L Garey,

Daniel J Ostlie, et al. “Morgagni hernia repair in children: comparison of

laparoscopic and open results.” J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, vol. 21,

no. 1, pp. 89-91, 2011. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[19] Georges Azzie, Kiki Maoate, Spencer

Beasley, et al. “A simple technique of laparoscopic full-thickness anterior

abdominal wall repair of retrosternal (Morgagni) hernias.” J Pediatr Surg,

vol. 38, no. no. 5, pp. 768-770, 2003. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[20] Sanjeev Dutta, Craig T “Albanese Use

of a prosthetic patch for laparoscopic repair of Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia

in children.” J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, vol. 17, no. 3, pp.

391-394, 2007. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[21] G. Greca, P. Fisichella, L. Greco, et

al. “A new simple laparoscopic-extracorporeal technique for the repair of a

Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia.” Surg Endosc, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 99,

2001. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[22] R L Hussong Jr, R J Landreneau, F H

Cole Jr “Diagnosis and repair of a Morgagni hernia with video-assisted thoracic

surgery.” Ann Thorac Surg, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 1474-1475, 1997. View at:

Publisher Site | PubMed

[23] M Anderberg, C Clementson Kockum, E

Arnbjornsson “Morgagni hernia repair in a small child using da Vinci robotic

instruments--a case report.” Eur J Pediatr Surg, vol. 19, no. 2, pp.

110-112, 2009. View at: Publisher

Site | PubMed

[24] Engin Yilmaz, Cagatay Evrim Afsarlar, Derya Erdogan, et al. “Outpatient single-port laparoscopic percutaneous Morgagni hernia repair assisted by an optical forceps.” Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 182-187, 2017. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed

[25] Paul D Danielson, Nicole M Chandler “Single-port laparoscopic repair of a Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia in a pediatric patient: advancement in single-port technology allows effective intracorporeal suturing.” J Pediatr Surg, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. E21-E24, 2010. View at: Publisher Site | PubMed